Random numbers are used everywhere, from facilitating lotteries, to simulating the weather or behaviour of materials, and ensuring secure data exchange between infrastructure and vehicles in intelligent transport systems (C-ITS).

Perhaps most importantly though, randomness is at the core of the security we all rely upon for transacting safely on the internet. Specifically, random numbers are used in the creation of secure cryptographic keys for encrypting data to safeguard its confidentiality, integrity and authenticity.

Random numbers are provided via random number generators (RNGs) that utilise a source of entropy (randomness) and an algorithm to generate random numbers. A number of RNG types exist based on the method of implementation (e.g. hardware and/or software).

Pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs)

PRNGs that rely purely on software can be cost-effective, but are intrinsically deterministic and given the same seed will produce the exact same sequence of random numbers (and due to memory constraints, this sequence will eventually repeat) – whilst the output of the PRNG may be statistically random, its behaviour is entirely predictable.

An attacker able to guess which PRNG is being used can deduce its state by observing the output sequence and thereby predict each random number – and this can be as small as 624 observations in the case of common PRNGs such as the Mersenne Twister MT19937. Moreover, an unfortunate choice of seed can lead to a short cycle length before the number sequence repeats which again opens the PRNG to attack. In short, PRNGs are inherently vulnerable and far from ideal for cryptography.

True random number generators (TRNGs)

TRNGs extract randomness (entropy) from a physical source and use this to generate a sequence of random numbers that in theory are highly unpredictable. Certainly they address many of the shortcomings of PRNGs, but they’re not perfect either.

In many TRNGs, the entropy source is based on thermal or electrical noise, or jitter in an oscillator, any of which can be manipulated by an attacker able to control the environment in which the TRNG is operating (e.g., temperature, EMF noise or voltage modulation).

Given the need to sample the entropy source, a TRNG can be slow in operation, and fundamentally limited by the nature of the entropy pool – a poorly designed implementation or choice of entropy can result in the entropy pool quickly becoming exhausted. In such a scenario, the TRNG has the choice of either reducing the amount of entropy used for generating each random number (compromising security) or scaling back the number of random numbers it generates.

Either situation could result in the same or similar random numbers being output until the entropy pool is replenished – a serious vulnerability that can be addressed through in-built health checks, but with the risk that output is ceased hence opening the TRNG up to denial-of-service attacks. Ring-oscillator based TRNGs, for instance, have a hard limit in how fast they can be run, and if more entropy is sought by combining a few in parallel they can produce similar outputs hence undermining their usefulness.

IoT devices in particular often have difficulty gathering sufficient entropy during initialisation to generate strong cryptographic keys given the lack of entropy sources in these simple devices, hence can be forced to use hard-coded keys, or seed the RNG from unique (but easy to guess) identifiers such as the device’s MAC address, both of which seriously undermines security robustness.

Ideally, RNGs need an entropy source that is completely unpredictable and chaotic, not influenced by external environmental factors, able to provide random bits in abundance to service a large volume of requests and facilitate stronger keys, and service these requests quickly and at high volume.

Quantum random number generators (QRNGs)

QRNGs are a special class of RNG that utilise Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle (an inability to know the position and speed of a photon or electron with perfect accuracy) to provide a pure source of entropy and therefore address all the aforementioned requirements.

Not only do they provide a provably random entropy source based on the laws of physics, QRNGs are also intrinsically high entropy hence able to deliver truly random bit sequences and at high speed thereby enabling QRNGs to run much faster than other TRNGs, and more efficiently than PRNGs across high volume applications.

They are also more resistant to environmental factors, and thereby at less risk from external manipulation, whilst also being able to operate reliably in EMF noisy environments such as data centres for serving random numbers to thousands of servers realtime.

But not all QRNGs are created equal; poor design in the physical construction and/or processing circuitry can compromise randomness or reduce the level of entropy resulting in system failure at high volumes. QRNG designs embracing sophisticated silicon photonics in an attempt to create high entropy sources can become cost prohibitive in comparison to established RNGs, whilst other designs often have size and heat constraints.

Introducing Crypta Labs

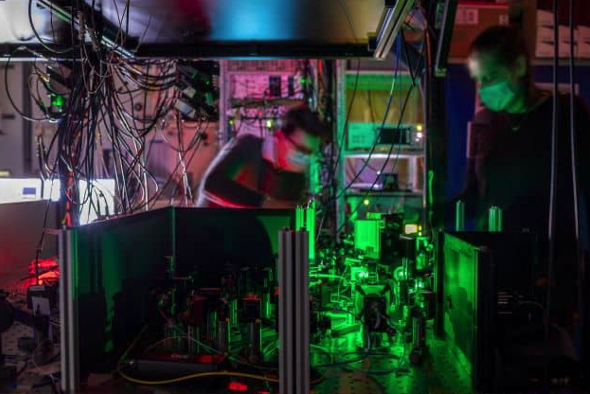

Careful design and robustness in implementation is therefore vital – Crypta Labs have been pioneering in quantum technology since 2014 and through their research have developed a unique solution utilising readily available components that makes use of quantum photonics as a source of entropy to produce a state-of-the-art QRNG capable of delivering quantum random numbers at very high speeds and easily integrated into existing systems. Blueshift Memory is an early adopter of the technology, creating a cybersecurity memory solution that will be capable of countering threats from quantum computing.

Rapid advances in compute power are undermining traditional cryptographic approaches and exploiting any weakness; even a slight imperfection in the random number generation can be catastrophic. Migrating to QRNGs reduces this threat and provides resiliency against advances in classical compute and the introduction of basic quantum computers expected over the next few years. In time, quantum computers will advance sufficiently to break the encryption algorithms themselves, but such computers will require tens of millions of physical qubits and therefore are unlikely to materialise for another 10 years or more.

Post-quantum cryptography (PQC) algorithms

In preparation for this quantum future, an activity spearheaded by NIST in the US with input from academia and the private sector (e.g., IBM, ARM, NXP, Infineon) is developing a set of PQC algorithms that will be safe against this threat. A component part of ensuring these PQC algorithms are quantum-safe involves moving to much larger key sizes, hence a dependency on QRNGs able to deliver sufficiently high entropy at scale.

In summary, a transition by hardware manufacturers (servers, firewalls, routers etc.) to incorporate QRNGs at the board level addresses the shortcomings of existing RNGs whilst also providing quantum resilience for the coming decade. Not only are they being adopted by large corporates such as Alibaba, they also form a component part of the White House’s strategy to combat the quantum threat in the US.

Given that QRNGs are superior to other TRNGs, can contribute to future-proofing cryptography for the next decade, and are now cost effective and easy to implement in the case of Crypta Lab’s solution, they really are a no-brainer.

An introduction from our CTO

Whilst security is undoubtedly important, fundamentally it’s a business case based on the time-value depreciation of the asset being protected, which in general leads to a design principle of “it’s good enough” and/or “it will only be broken in a given timeframe”.

At the other extreme, history has given us many examples where reliance on theoretical certainty fails due to unknowns. One such example being the Titanic which was considered by its naval architects as unsinkable. The unknown being the iceberg!

It is a simple fact that weaker randomness leads to weaker encryption, and with the inexorable rise of compute power due to Moore’s law, the barriers to breaking encryption are eroding. And now with the advent of the quantum-era, cyber-crime is about to enter an age in which encryption when done less than perfectly (i.e. lacking true randomness) will no longer be ‘good enough’ and become ever more vulnerable to attack.

In the following, Bloc’s Head of Research David Pollington takes a deeper dive into the landscape of secure communications and how it will need to evolve to combat the threat of the quantum-era. Bloc’s research findings inform decisions on investment opportunities.

Setting the scene

Much has been written on quantum computing’s threat to encryption algorithms used to secure the Internet, and the robustness of public-key cryptography schemes such as RSA and ECDH that are used extensively in internet security protocols such as TLS.

These schemes perform two essential functions: securely exchanging keys for encrypting internet session data, and authenticating the communicating partners to protect the session against Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks.

The security of these approaches relies on either the difficulty of factoring integers (RSA) or calculating discrete logarithms (ECDH). Whilst safe against the ‘classical’ computing capabilities available today, both will succumb to Shor’s algorithm on a sufficiently large quantum computer. In fact, a team of Chinese scientists have already demonstrated an ability to factor integers of 48bits with just 10 qubits using Schnorr’s algorithm in combination with a quantum approximate optimization to speed-up factorisation – projecting forwards, they’ve estimated that 372 qubits may be sufficient to crack today’s RSA-2048 encryption, well within reach over the next few years.

The race is on therefore to find a replacement to the incumbent RSA and ECDH algorithms… and there are two schools of thought: 1) Symmetric encryption + Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), or 2) Post Quantum Cryptography (PQC).

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)

In contrast to the threat to current public-key algorithms, most symmetric cryptographic algorithms (e.g., AES) and hash functions (e.g., SHA-2) are considered to be secure against attacks by quantum computers.

Whilst Grover’s algorithm running on a quantum computer can speed up attacks against symmetric ciphers (reducing the security robustness by a half), an AES block-cipher using 256-bit keys is currently considered by the UK’s security agency NCSC to be safe from quantum attack, provided that a secure mechanism is in place for sharing the keys between the communicating parties – Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) is one such mechanism.

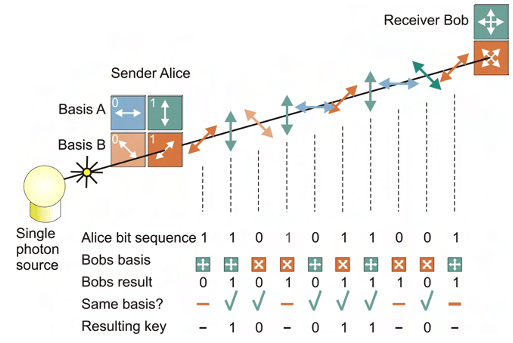

Rather than relying on the security of underlying mathematical problems, QKD is based on the properties of quantum mechanics to mitigate tampering of the keys in transit. QKD uses a stream of single photons to send each quantum state and communicate each bit of the key.

However, there are a number of implementation considerations that affect its suitability:

Integration complexity & cost

- QKD transmits keys using photons hence is reliant on a suitable optical fibre or free-space (satellite) optical link – this adds complexity and cost, precludes use in resource-constrained edge devices (such as mobile phones and IoT devices), and reduces flexibility in applying upgrades or security patches

Distance constraints

- A single QKD link over optical fibre is typically limited to a few 100 km’s with a sweet spot in the 20–50 km range

- Range can be extended using quantum repeaters, but doing so entails additional cost, security risks, and threat of interception as the data is decoded to classical bits before re-encrypting and transmitting via another quantum channel; it also doesn’t scale well for constructing multi-user group networks

- Alternative, greater range can be achieved via satellite links, but at significant additional cost

- A fully connected entanglement-based quantum communication network is theoretically possible without requiring trusted nodes, but is someway off commercialisation and will be dependent again on specialist hardware

Authentication

- A key tenet of public-key schemes is mutual authentication of the communicating parties – QKD doesn’t inherently include this, and hence is reliant on either encapsulating the symmetric key using RSA or ECDH (which, as already discussed, isn’t quantum-safe), or using pre-shared keys exchanged offline (which adds complexity)

- Given that the resulting authenticated channel could then be used in combination with AES for encrypting the session data, to some extent this negates the need for QKD

DoS attack

- The sensitivity of QKD channels to detecting eavesdropping makes them more susceptible to denial of service (DoS) attacks

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC)

Rather than replacing existing public key infrastructure, an alternative is to develop more resilient cryptographic algorithms.

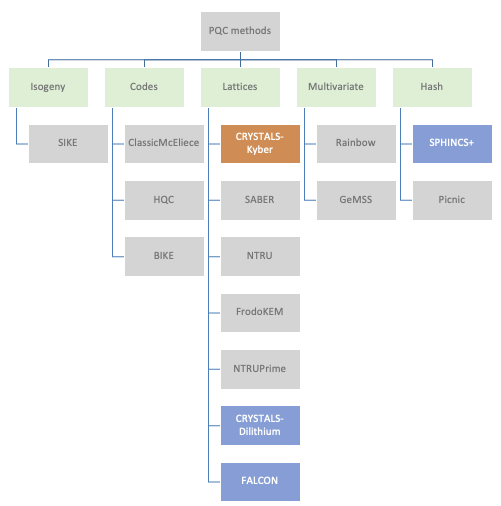

With that in mind, NIST have been running a collaborative activity with input from academia and the private sector (e.g., IBM, ARM, NXP, Infineon) to develop and standardise new algorithms deemed to be quantum-safe.

A number of mathematical approaches have been explored with a large variation in performance. Structured lattice-based cryptography algorithms have emerged as prime candidates for standardisation due to a good balance between security, key sizes, and computational efficiency. Importantly, it has been shown that lattice-based algorithms can be implemented on low-power IoT edge devices (e.g., using Cortex M4) whilst maintaining viable battery runtimes.

Four algorithms have been short-listed by NIST: CRYSTALS-Kyber for key establishment, CRYSTALS-Dilithium for digital signatures, and then two additional digital signature algorithms as fallback (FALCON, and SPHINCS+). SPHINCS+ is a hash-based backup in case serious vulnerabilities are found in the lattice-based approach.

NIST aims to have the PQC algorithms fully standardised by 2024, but have released technical details in the meantime so that security vendors can start working towards developing end-end solutions as well as stress-testing the candidates for any vulnerabilities. A number of companies (e.g., ResQuant, PQShield and those mentioned earlier) have already started developing hardware implementations of the two primary algorithms.

Commercial landscape

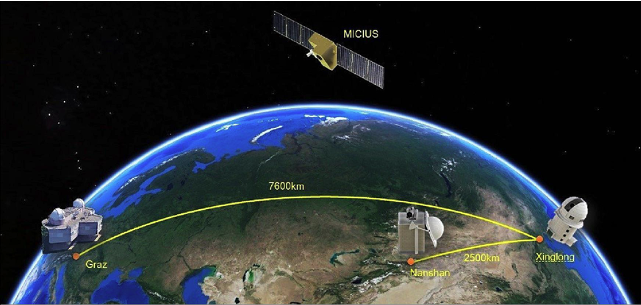

QKD has made slow progress in achieving commercial adoption, partly because of the various implementation concerns outlined above. China has been the most active, the QUESS project in 2016 creating an international QKD satellite channel between China and Vienna, and in 2017 the completion of a 2000km fibre link between Beijing and Shanghai. The original goal of commercialising a European/Asian quantum-encrypted network by 2020 hasn’t materialised, although the European Space Agency is now aiming to launch a quantum satellite in 2024 that will spend three years in orbit testing secure communications technologies.

BT has recently teamed up with EY (and BT’s long term QKD tech partner Toshiba) on a two year trial interconnecting two of EY’s offices in London, and Toshiba themselves have been pushing QKD in the US through a trial with JP Morgan.

Other vendors in this space include ID Quantique (tech provider for many early QKD pilots), UK-based KETS, MagiQ, Qubitekk, Quintessance Labs and QuantumCtek (commercialising QKD in China). An outlier is Arqit; a QKD supporter and strong advocate for symmetric encryption that addresses many of the QKD implementation concerns through its own quantum-safe network and has partnered with Virgin Orbit to launch five QKD satellites, beginning in 2023.

Given the issues identified with QKD, both the UK (NCSC) and US (NSA) security agencies have so far discounted QKD for use in government and defence applications, and instead are recommending post-quantum cryptography (PQC) as the more cost effective and easily maintained solution.

There may still be use cases (e.g., in defence, financial services etc.) where the parties are in fixed locations, secrecy needs to be guaranteed, and costs are not the primary concern. But for the mass market where public-key solutions are already in widespread use, the best approach is likely to be adoption of post-quantum algorithms within the existing public-key frameworks once the algorithms become standardised and commercially available.

Introducing the new cryptographic algorithms though will have far reaching consequences with updates needed to protocols, schemes, and infrastructure; and according to a recent World Economic Forum report, more than 20 billion digital devices will need to be upgraded or replaced.

Widespread adoption of the new quantum-safe algorithms may take 10-15 years, but with the US, UK, French and German security agencies driving the use of post-quantum cryptography, it’s likely to become defacto for high security use cases in government and defence much sooner.

Organisations responsible for critical infrastructure are also likely to move more quickly – in the telco space, the GSMA, in collaboration with IBM and Vodafone, have recently launched the GSMA Post-Quantum Telco Network Taskforce. And Cloudflare has also stepped up, launching post-quantum cryptography support for all websites and APIs served through its Content Delivery Network (19+% of all websites worldwide according to W3Techs).

Importance of randomness

Irrespective of which encryption approach is adopted, their efficacy is ultimately dependent on the strength of the cryptographic key used to encrypt the data. Any weaknesses in the random number generators used to generate the keys can have catastrophic results, as was evidenced by the ROCA vulnerability in an RSA key generation library provided by Infineon back in 2017 that resulted in 750,000 Estonian national ID cards being compromised.

Encryption systems often rely upon Pseudo Random Number Generators (PRNG) that generate random numbers using mathematical algorithms, but such an approach is deterministic and reapplication of the seed generates the same random number.

True Random Number Generators (TRNGs) utilise a physical process such as thermal electrical noise that in theory is stochastic, but in reality is somewhat deterministic as it relies on post-processing algorithms to provide randomness and can be influenced by biases within the physical device. Furthermore, by being based on chaotic and complex physical systems, TRNGs are hard to model and therefore it can be hard to know if they have been manipulated by an attacker to retain the “quality of the randomness” but from a deterministic source.Ultimately, the deterministic nature of PRNGs and TRNGs opens them up to quantum attack.

A further problem with TRNGs for secure comms is that they are limited to either delivering high entropy (randomness) or high throughput (key generation frequency) but struggle to do both. In practise, as key requests ramp to serve ever-higher communication data rates, even the best TRNGs will reach a blocking rate at which the randomness is exhausted and keys can no longer be served. This either leads to downtime within the comms system, or the TRNG defaults to generating keys of 0 rendering the system highly insecure; either eventuality results in the system becoming highly susceptible to denial of service attacks.

Quantum Random Number Generators (QRNGs) are a new breed of RNGs that leverage quantum effects to generate random numbers. Not only does this achieve full entropy (i.e., truly random bit sequences) but importantly can also deliver this level of entropy at a high throughput (random bits per second) hence ideal for high bandwidth secure comms.

Having said that, not all QRNGs are created equal – in some designs, the level of randomness can be dependent on the physical construction of the device and/or the classical circuitry used for processing the output, either of which can result in the QRNG becoming deterministic and vulnerable to quantum attack in a similar fashion to the PRNG and TRNG. And just as with TRNGs, some QRNGs can run out of entropy at high data rates leading to system failure or generation of weak keys.

Careful design and robustness in implementation is therefore vital – Crypta Labs have been pioneering in quantum tech since 2014 and through their research have designed a QRNG that can deliver hundreds of megabits per second of full entropy whilst avoiding these implementation pitfalls.

Summary

Whilst time estimates vary, it’s considered inevitable that quantum computers will eventually reach sufficient maturity to beat today’s public-key algorithms – prosaically dubbed Y2Q. The Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) have started a countdown to April 14 2030 as the date by which they believe Y2Q will happen.

QKD was the industry’s initial reaction to counter this threat, but whilst meeting the security need at a theoretical level, has arguably failed to address implementation concerns in a way which is cost effective, scalable and secure for the mass market, at least to the satisfaction of NCSC and NSA.

Proponents of QKD believe key agreement and authentication mechanisms within public-key schemes can never be fully quantum-safe, and to a degree they have a point given the recent undermining of Rainbow, one of the short-listed PQC candidates. But QKD itself is only a partial solution.

The collaborative project led by NIST is therefore the most likely winner in this race, and especially given its backing by both the NSA and NCSC. Post-quantum cryptography (PQC) appears to be inherently cheaper, easier to implement, and deployable on edge devices, and can be further strengthened through the use of advanced QRNGs. Deviating away from the current public-key approach seems unnecessary compared to swapping out the current algorithms for the new PQC alternatives.

Looking to the future

Setting aside the quantum threat to today’s encryption algorithms, an area ripe for innovation is in true quantum communications, or quantum teleportation, in which information is encoded and transferred via the quantum states of matter or light.

It’s still early days, but physicists at QuTech in the Netherlands have already demonstrated teleportation between three remote, optically connected nodes in a quantum network using solid-state spin qubits.

Longer term, the goal is to create a ‘quantum internet’ – a network of entangled quantum computers connected with ultra-secure quantum communication guaranteed by the fundamental laws of physics.

When will this become a reality? Well, as with all things quantum, the answer is typically ‘sometime in the next decade or so’… let’s see.